Who Was Martin Luther King Jr?

Martin Luther King Jr. was a Baptist minister and civil-rights activist who had a seismic impact on race relations in the United States, beginning in the mid-1950s.

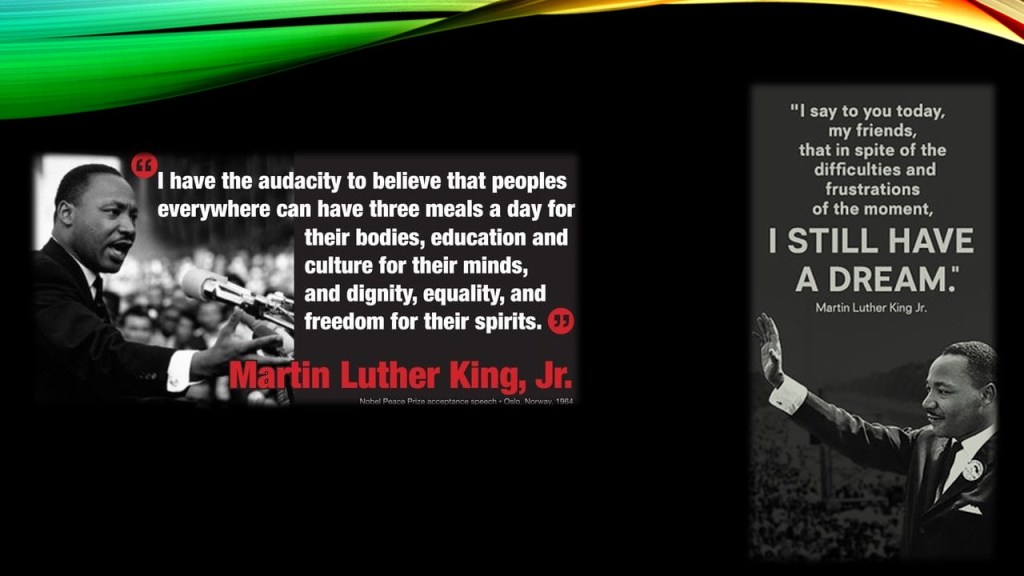

Among his many efforts, King headed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Through his activism and inspirational speeches, he played a pivotal role in ending the legal segregation of African American citizens in the United States, as well as the creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

King won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, among several other honors. He continues to be remembered as one of the most influential and inspirational African American leaders in history.

Early Life

Born as Michael King Jr. on January 15, 1929, Martin Luther King Jr. was the middle child of Michael King Sr. and Alberta Williams King.

The King and Williams families had roots in rural Georgia. Martin Jr.’s grandfather, A.D. Williams, was a rural minister for years and then moved to Atlanta in 1893.

He took over the small, struggling Ebenezer Baptist church with around 13 members and made it into a forceful congregation. He married Jennie Celeste Parks and they had one child that survived, Alberta.

King had an older sister, Willie Christine, and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel Williams King. The King children grew up in a secure and loving environment. Martin Sr. was more the disciplinarian, while his wife’s gentleness easily balanced out the father’s strict hand.

Though they undoubtedly tried, King’s parents couldn’t shield him completely from racism. Martin Sr. fought against racial prejudice, not just because his race suffered, but because he considered racism and segregation to be an affront to God’s will. He strongly discouraged any sense of class superiority in his children which left a lasting impression on Martin Jr. Growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, King entered public school at age five. In May 1936 he was baptized, but the event made little impression on him.

In May 1941, King was 12 years old when his grandmother, Jennie, died of a heart attack. The event was traumatic for King, more so because he was out watching a parade against his parents’ wishes when she died. Distraught at the news, young King jumped from a second-story window at the family home, allegedly attempting suicide.

King attended Booker T. Washington High School, where he was said to be a precocious student. He skipped both the ninth and eleventh grades, and entered Morehouse College in Atlanta at age 15, in 1944. He was a popular student, especially with his female classmates, but an unmotivated student who floated through his first two years.

Although his family was deeply involved in the church and worship, King questioned religion in general and felt uncomfortable with overly emotional displays of religious worship. This discomfort continued through much of his adolescence, initially leading him to decide against entering the ministry, much to his father’s dismay.

But in his junior year, King took a Bible class, renewed his faith and began to envision a career in the ministry. In the fall of his senior year, he told his father of his decision.

Education and Spiritual Growth

In 1948, King earned a sociology degree from Morehouse College and attended the liberal Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. He thrived in all his studies, and was valedictorian of his class in 1951, and elected student body president. He also earned a fellowship for graduate study. But King also rebelled against his father’s more conservative influence by drinking beer and playing pool while at college. He became involved with a white woman and went through a difficult time before he could break off the affair.

During his last year in seminary, King came under the guidance of Morehouse College President Benjamin E. Mays who influenced King’s spiritual development. Mays was an outspoken advocate for racial equality and encouraged King to view Christianity as a potential force for social change. After being accepted at several colleges for his doctoral study, King enrolled at Boston University.

During the work on his doctorate, King met Coretta Scott, an aspiring singer and musician at the New England Conservatory school in Boston. They were married in June 1953 and had four children, Yolanda, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott and Bernice.

In 1954, while still working on his dissertation, King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church of Montgomery, Alabama. He completed his Ph.D. and earned his degree in 1955. King was only 25 years old.

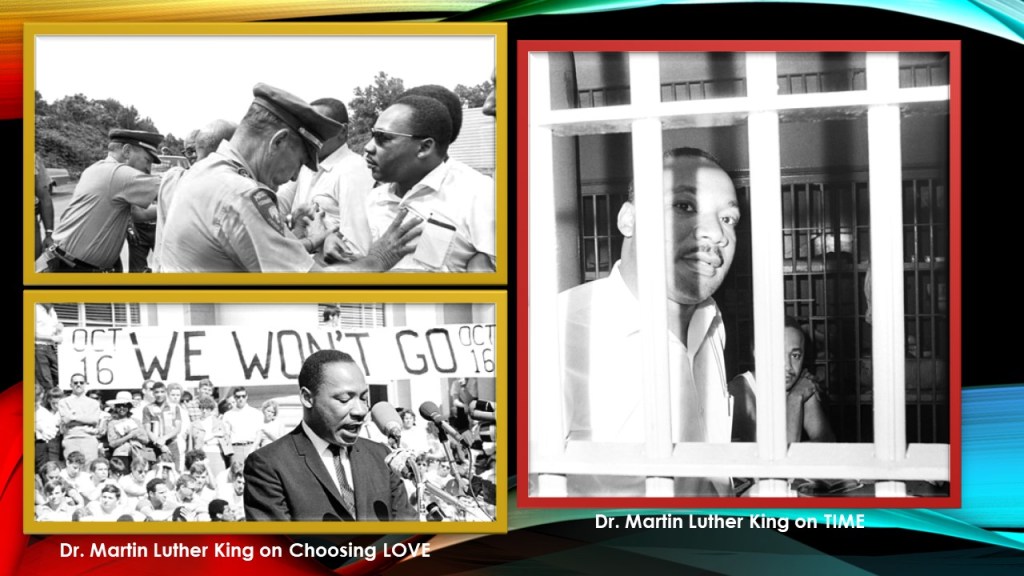

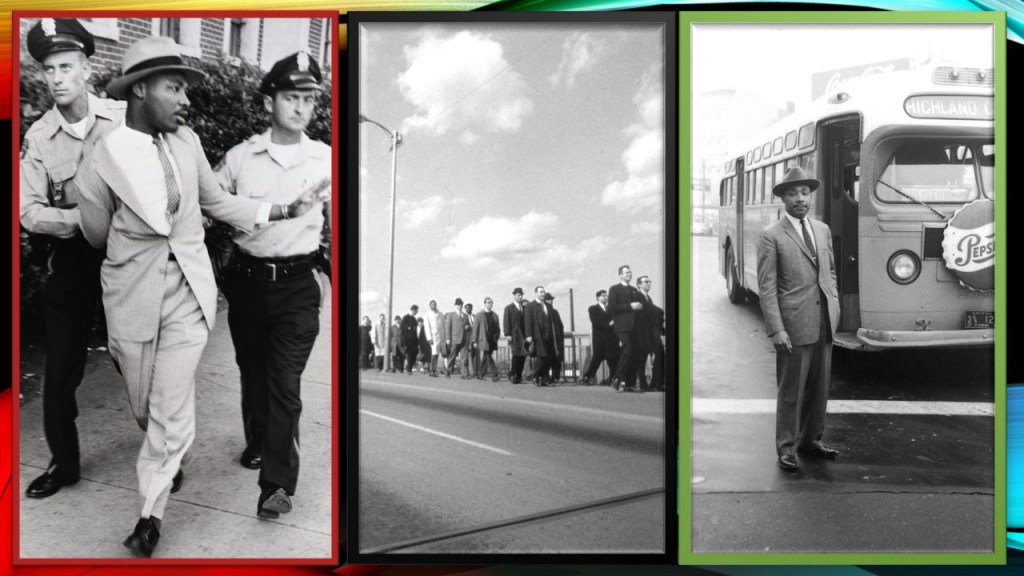

Montgomery Bus Boycott

On March 2, 1955, a 15-year-old girl refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery city bus in violation of local law. Teenager Claudette Colvin was then arrested and taken to jail.

At first, the local chapter of the NAACP felt they had an excellent test case to challenge Montgomery’s segregated bus policy. But then it was revealed that Colvin was pregnant and civil rights leaders feared this would scandalize the deeply religious Black community and make Colvin (and, thus the group’s efforts) less credible in the eyes of sympathetic white people.

On December 1, 1955, they got another chance to make their case. That evening, 42-year-old Rosa Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus to go home after an exhausting day at work. She sat in the first row of the “colored” section in the middle of the bus. As the bus traveled its route, all the seats in the white section filled up, then several more white passengers boarded the bus.

The bus driver noted that there were several white men standing and demanded that Parks and several other African Americans give up their seats. Three other African American passengers reluctantly gave up their places, but Parks remained seated.

The driver asked her again to give up her seat and again she refused. Parks was arrested and booked for violating the Montgomery City Code. At her trial a week later, in a 30-minute hearing, Parks was found guilty and fined $10 and assessed $4 court fee.

On the night that Parks was arrested, E.D. Nixon, head of the local NAACP chapter met with King and other local civil rights leaders to plan a Montgomery Bus Boycott. King was elected to lead the boycott because he was young, well-trained with solid family connections and had professional standing. But he was also new to the community and had few enemies, so it was felt he would have strong credibility with the Black community.

In his first speech as the group’s president, King declared, “We have no alternative but to protest. For many years we have shown an amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice.”

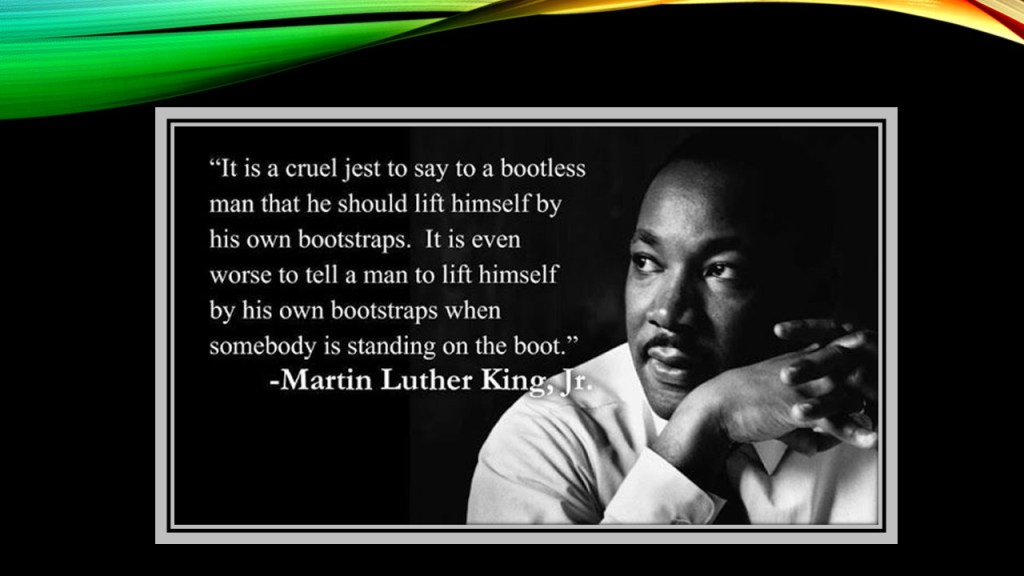

King’s skillful rhetoric put new energy into the civil rights struggle in Alabama. The bus boycott involved 382 days of walking to work, harassment, violence, and intimidation for Montgomery’s African American community. Both King’s and Nixon’s homes were attacked.

But the African American community also took legal action against the city ordinance arguing that it was unconstitutional based on the Supreme Court’s “separate is never equal” decision in Brown v. Board of Education. After being defeated in several lower court rulings and suffering large financial losses, the city of Montgomery lifted the law mandating segregated public transportation.

The Fight for Martin Luther King Jr. Day

It took 15 years of fighting for MLK Day to be declared a national holiday

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the entire nation pauses in remembrance of a civil rights hero. At least, that’s the point of the federal holiday that takes place on the third Monday of each January. MLK Day was designed to honor the activist and minister assassinated in 1968, whose accomplishments have continued to inspire generations of Americans.

But though the holiday now graces the United States’ federal calendar and affects countless offices, schools, businesses and other public and private spaces, it wasn’t always observed. The fight for a holiday in Martin Luther King Jr.’s honor was an epic struggle in and of itself—and it continues to face resistance in the form of competing holidays to leaders of the Confederacy.

King was the first modern private citizen to be honored with a federal holiday, and for many familiar with his non-violent leadership of the civil rights movement, it made sense to celebrate him. But for others, the suggestion that King—a Black minister who was vilified during his life and gunned down when he was just 39 years old—deserved a holiday was nothing short of incendiary.

The first push for a holiday honoring King took place just four days after his assassination. John Conyers, then a Democratic Congressman from Michigan, took to the floor of Congress to insist on a federal holiday in King’s honor. However, the request fell on deaf ears.

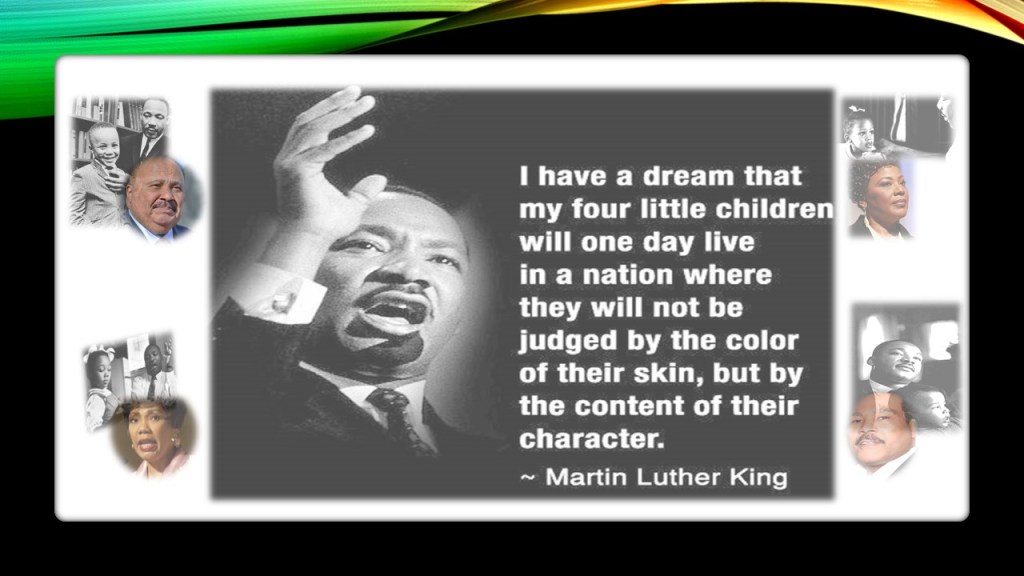

The tide finally turned in the early 1980s. By then, the CBC had collected six million signatures in support of a federal holiday in honor of King. Stevie Wonder had written a hit song, “Happy Birthday,” about King, which drove an upswell of public support for the holiday. And in 1983, as civil rights movement veterans gathered in Washington to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the March on Washington, King’s seminal “I Have a Dream” speech, and the 15th anniversary of his murder, something shook loose.

When the legislation once again made it to the floor, it was filibustered by Jesse Helms, the Republican senator from North Carolina. As Helms pressed to introduce FBI smear material on King—whom the agency had spent years trying to pinpoint as a Communist and threat to the United States during the height of his influence—into the Congressional record, tensions boiled over. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the senator from New York, brought the materials onto the floor, then dropped them to the ground in disgust in a pivotal moment of the debate.

The bill passed with ease the following day (78-22) and President Ronald Reagan immediately signed the legislation.

But though the first federal holiday was celebrated in 1986, it took years for observance to filter through to every state. Several Southern states promptly combined Martin Luther, King Jr. Day with holidays that uplifted Confederate leader Robert E. Lee, who was born on January 19. Arizona initially observed the holiday, then rescinded it, leading to a years-long scuffle over whether to celebrate King that ended in multiple public referenda, major boycotts of the state, and a final voter registration push that helped propel a final referendum toward success in 1992.

It wasn’t until 2000 that every state in the Union finally observed Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Today, the holiday is still celebrated in conjunction with a celebration of Confederate figures in some states—but after three decades of contention and controversy, it is observed.

Remembering Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, monument built between 2009 and 2011 in Washington, D.C., honoring the American Baptist minister, social activist, and Nobel Peace Prize winner Martin Luther King, Jr., who led the civil rights movement in the United States from the mid-1950s until his death by assassination in 1968. The monument is located along the west bank of the Tidal Basin, near the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial and not far from the Lincoln Memorial, from which King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington in August, 1963.

The memorial, built at a cost of about $120 million (raised through donations by individuals, organizations, and corporations), was officially opened to the public in August 2011. It was the first monument on the Mall or in its associated memorial parks to be dedicated to an African American. The effort to establish the memorial was initiated in the 1980s by Alpha Phi Alpha, a historically black fraternity, and in 1996 President Bill Clinton signed congressional legislation authorizing the establishment of the memorial. The memorial’s official address, 1964 Independence Avenue, referencing the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act.

In 2000, the judges selected ROMA Design Group’s plan for a stone with Dr. King’s image emerging from a mountain. The plan’s theme referenced a line from King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech: “With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” The final design includes a massive carved mountain with a slice pulled out of it, symbolizing the “Stone of Hope” being hewn from the “Mountain of Despair.” Reinforcing this motif, the edges of the Stone of Hope and the Mountain of Despair incorporate scrape marks to symbolize the struggle and movement, as well as an engraving of the words “Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.” Visitors may enter the memorial through the Mountain of Despair and tour the memorial reflecting on the struggle that Dr. King faced during his life, approaching the plaza where the Stone of Hope stands. In the stone, a carving of Dr. King gazes to the horizon, thoughtful and resolute.

The memorial’s location is also significant, enhancing the core of the “city beautiful” that Pierre L’Enfant envisioned in 1791, and the McMillan Plan expanded in 1901. The plans aimed to create an entire city to remind us “what we should be trying to achieve as a nation, as a society [and] as human beings on this planet.” For the “I Have a Dream” speech, King stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and referenced the Declaration of Independence, penned by Thomas Jefferson. King leveraged the power of place to appeal to core American values that all Americans held dear, highlighting the injustice perpetuated by segregation. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial’s location along the line connecting the Thomas Jefferson and Lincoln Memorials helps to reinforce the connection between these three leaders at three important moments for civil rights in our nation’s history: from the promise that “all men are created equal,” to the freeing of the slaves, to the final push for full and equal rights.